When the American Civil War began in 1861, Walt Whitman was already one of the nation’s most distinctive literary voices. His Leaves of Grass had celebrated democracy and the spirit of the American people. But nothing in his earlier work could have prepared him for the human cost of the conflict that soon engulfed the country. The war would have a direct influence on Whitman’s poetry and transform his entire understanding of America and the role of the poet within it.

If you would like to visit key battlefields as part of your study of the Civil War, consider joining us on one of our American Civil War Tours.

From Observer to Witness

Whitman’s connection to the war began in December 1862, when he learned that his younger brother George, a soldier in the Union Army, had been wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Fearing the worst, he traveled south in search of him. After days of anxious searching among the field hospitals and camps, Whitman found George alive and only lightly wounded. But what he saw around him – the carnage, the suffering, the makeshift hospitals overflowing with the injured and dying – made an indelible impression.

Whitman decided not to return home. Instead, he went to Washington, D.C., and began visiting military hospitals almost every day. He estimated that over the next three years he cared for or comforted more than 80,000 soldiers.

A Poet in the Wards

Whitman’s self-appointed mission was simple: to bring comfort. He wrote letters for men too weak to hold a pen, brought them small gifts, sat beside them as they slept, and often stayed with them during their dying moments. His presence in the hospitals became familiar – his tall frame, kind voice, and quiet manner a source of solace to countless young soldiers far from home.

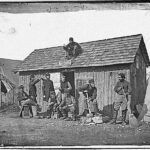

In his notes, Whitman recorded the details of those encounters with unflinching honesty. He described the “great humanity” of the wounded, the smell of antiseptic and blood, the piles of amputated limbs outside hospital tents. Yet his focus was always on the individual, on the soldier as a person rather than a statistic.

These experiences gave Whitman a new sense of America’s shared humanity. The soldiers he met – farmers, laborers, immigrants, and clerks – became symbolic of the American nation in a way that transcended politics and ideology.

The War in Verse

From this period of service came some of Whitman’s most enduring poetry. His 1865 collection Drum-Taps captures the full emotional range of the war, from the excitement of early mobilization to the grief that followed. Poems like “Beat! Beat! Drums!” reflect the patriotic energy of the time, while “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night” and “A Sight in Camp in the Daybreak Gray and Dim” express profound compassion for the fallen.

After Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Whitman wrote “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” a work that stands among the great elegies in world literature. In it, Whitman transformed personal mourning into a national act of remembrance.

Legacy of a Witness

Whitman’s years as a nurse left him physically exhausted and financially strained, but they also deepened his empathy and moral vision. In his later prose work Specimen Days (1882), he reflected on his wartime experiences with the same mix of realism and reverence that defined his poetry.

He once wrote, “The real war will never get in the books.” Yet his writing comes closer than most to capturing its human truth. Unlike generals who wrote of strategy or politicians who spoke of causes, Whitman bore witness to the war’s everyday suffering and quiet heroism.

A Lasting Connection to Virginia

It was Virginia, at Fredericksburg, where Whitman’s journey into the heart of the war began. That trip changed not only his life but the way future generations would understand the Civil War. In Whitman’s poems and prose, the war is more than a report of battles and victories; it is a tale of tenderness amid destruction and compassion amid chaos.

Standing on the fields of Fredericksburg today, one can contemplate the immense human cost behind the history. His words remind us that the truest memorials are not always monuments of stone, but acts of empathy and remembrance that keep the past alive.

Come and visit the battlefields for yourself. Book an American Civil War Tour in Virginia.