Known also as the Battle of Kellysville or Kelleysville, the Battle of Kelly’s Ford was a largely inconclusive engagement that presented both challenges and opportunities for the Union and Confederate forces.

Today, the American Battlefield Trust conserves and maintains 1,370 acres of the battlefield in Culpeper County.

Continue reading to learn more about the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, or book yourself a Guided Civil War Battlefield Tour in Virginia.

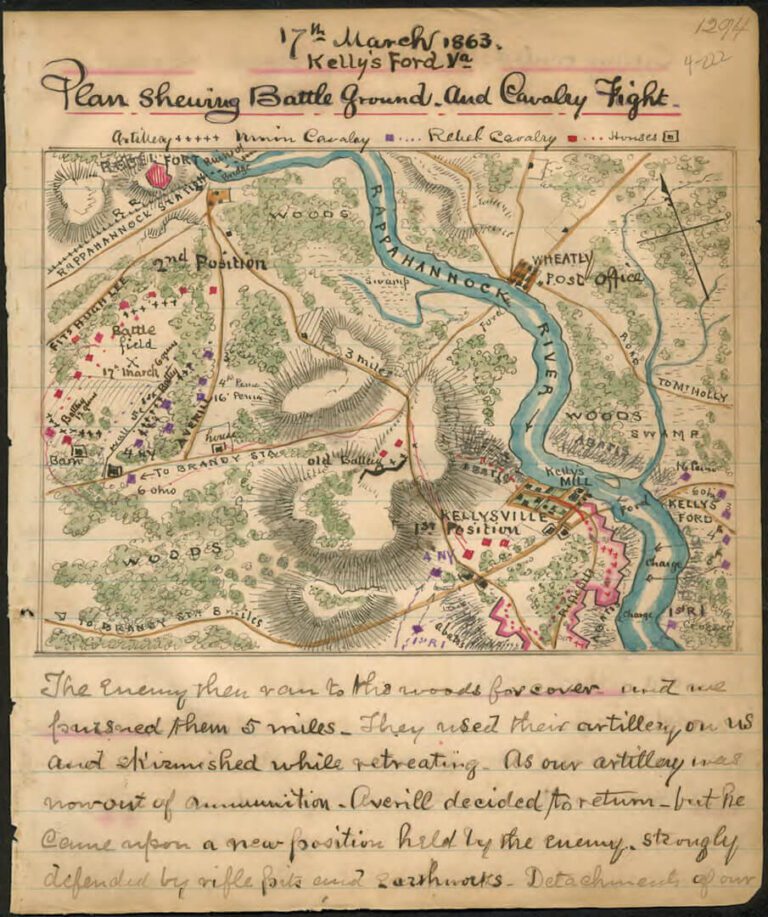

Before delving into the specifics of the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, it’s important to note that this site witnessed three distinct Civil War battles. The first, the Battle of Kelly’s Ford, took place on March 17, 1863. This was followed by the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, and the Second Battle of Rappahannock Station on November 7, 1863.

When touring with Battlefield Tours of Virginia, while the primary focus will be on the events of November 7, the earlier battles at this site will also be explored, making it a vital stop for Civil War history enthusiasts.

Often considered a precursor to the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Kelly’s Ford holds a unique position in Civil War history. On the eve of the battle, Union Brigadier General William Averell expressed his intent to rout or destroy the cavalry of Confederate Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, who had frequently raided Union positions.

Although Averell withdrew his forces before achieving a decisive victory, the engagement significantly boosted Union morale. In the days leading up to the battle, the Union Cavalry Corps, though better equipped and more numerous than their Confederate counterparts, lacked their enemy’s resolve.

In early March, Lee’s cavalry had conducted raids against Union camps along the Rappahannock River, prompting Averell to take action.

On March 16, 1863, he launched an offensive against Lee’s brigade, and by the next day, his advance guard had reached Kelly’s Ford, encountering 60 Confederate sharpshooters. Major Samuel E. Chamberlain’s brigade broke through, allowing Averell and his men to cross the river.

Initially outnumbered, the Confederates were bolstered by the coincidental arrival of Jeb Stuart and his artillery chief, Major John Pelham. Although not intended to fight that day, Pelham led a charge and was fatally wounded by artillery fire. Union brigades led by Duffie and Reno effectively pushed back the Confederates but failed to exploit their advantage.

By early evening, an exhausted Averell ordered a withdrawal, a decision later criticized by some who believed a prolonged attack could have decimated Lee’s forces. Despite the retreat, the battle proved the Union could confront and potentially defeat the Confederates.

The battle was particularly sorrowful for the Confederates due to the death of the highly regarded Major John Pelham, who succumbed to his injuries the following day. His loss deeply affected Jeb Stuart, who proposed to his wife that they name their next son John in his honor.

Despite their grief, the Confederates claimed a tactical victory and maintained control of the battlefield. In terms of casualties, the Union suffered 78 (6 killed, 50 wounded, 22 missing), while the Confederates had 133 casualties (11 killed, 88 wounded, 34 captured).

Ready to take your exploration of American Civil War history to the next level? Book a Guided Battlefield Tour in Virginia.

Ready to explore the battlefield for yourself? Browse our full selection of American Civil War Battlefield Tours.

Please contact us if you have any questions about our tours or services.